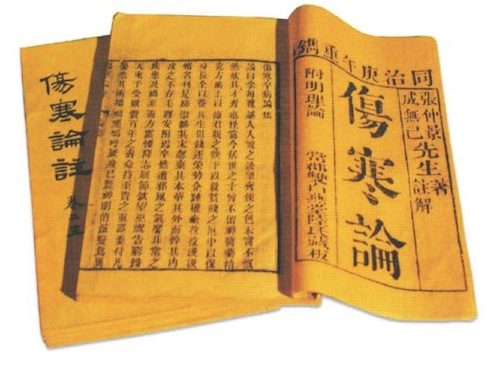

The Treatise of Cold Damage

Quite simply, the Shānghán Lùn(伤寒论), otherwise known as the Treatise on Cold Damage, is, in my opinion, the single greatest medical book ever written. If you’ve ever been to an acupuncturist or a practitioner of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), you’ve relived a legacy that traces back nearly 2,000 years to one man and one groundbreaking text. While the Nèijīng (黄帝内经) provides theoretical basis for TCM, it is the Shāng hán Lùn that takes that first takes theoretical basis and gives practitioners clear guidelines on how to apply those ideas into the clinic.

The book is actually required reading for all students of Traditional Chinese Medicine. To claim to practice Chinese Medicine and not imbibe oneself in the contents of the Shāng hán Lùn is tantamount to being a Christian without having gazed on a single page of the New Testament.

Zhang Zhongjing, The Physician-Sage

The Shang Han Lun’s authorship is credited to Zhāng Zhōngjǐng (张仲景), known also in Chinese culture as the Physician Sage (医圣 Yī Shèng). He did not just elaborate on how to diagnose and treat, he defined an entire medical paradigm still being practiced today.

Zhāng Zhōngjǐng, also known as Zhāng Jī (張機), was born in a time of great change in ancient China. The Han Dynasty was in its last breath, political institutions were breaking down, and seeds were being planted that would give rise to the chaotic era known as the Three Kingdoms. It was a rat race by territorial warlords taking the opportunity to grab for power, and the one who suffered most were the people.

Especially when epidemics occur.

Zhāng himself expressed his sorrow when, according to the introduction to the Shang Han Lun, two-thirds of his clan, which numbered about two hundred people, died in a short time, seven-tenths from Cold Damage. Out of this devastation, he made a vow to preserve effective methods and prevent future generations from enduring such loss.

Determined to “study the teachings of the ancients and gather the most effective formulas,” Zhāng compiled the Treatise on Cold Damage and Miscellaneous Diseases (Shānghán Zábìng Lùn, 傷寒雜病論) between 200 and 210 CE. Drawing from now-lost texts, folk prescriptions, and his clinical experience, he created a system that would redefine Chinese medicine forever.

Interlude: What is “Cold Damage?”

Before we go on, we must clarify what the term “Cold Damage” (Shānghán, 伤寒) means. The word “hán” (寒) here means cold. The word “Shāng” (伤) can be best explained by taking the modern word for wound – “Shāngkǒu” (伤口). Kou is used colloquially to mean mouth, but it can and also means opening. Literally, the word for wound can be said to be “opening caused by trauma or injury”.

In its narrow sense, it means diseases caused specifically by externally contracted pathogenic cold.1

In its broad sense, it refers to all externally contracted febrile (feverish) diseases, whether they are caused by wind, cold, summerheat, dampness, dryness, or fire.2

Compare the idea of Cold Damage to another used term in Chinese Medicine, “warm disease” or 溫病(wēnbìng). Briefly, Cold Damage can refer to any illness that is brought about by exposure to the elements – imagine a person getting muscle cramps or the flu after being out in the rain. In Warm Disease, the pathogens are usually more virulent, looking more like infectious epidemics than the seasonal flu.

On a side-note, the term Shānghán, 伤寒 has a different meaning in modern medical Chinese – Typhoid Fever. I have seen many subtitles on movies and TV dramas make this error.

Lost and Found

Not long after its completion, the chaos of wartime caused the original manuscript to be scattered and partially lost. For centuries, its wisdom was fragmented. In the Western Jin Dynasty, an imperial physician named Wang Shu-he collected the parts he could find on “cold damage” and compiled them into the Treatise on Cold Damage. During the Tang Dynasty, the famous physician Sūn Sīmiǎo (孫思邈)only had a portion of the text when writing his first book, but later in life, he collected the treatise in its entirety while writing the Supplement to ‘Important Formulas Worth a Thousand Gold Pieces’ (Qiān Jin Yì Fāng, 千金翼方). Finally, in the Northern Song Dynasty (around 1065 AD), imperial scholars including Lín Yì (林亿) and Gāo Bǎo-héng (高保衡) restored and edited the version now recognized as the Treatise on Cold Damage.

The other part of Zhang’s original work, the “miscellaneous diseases” section, was also recovered and printed separately. Today, it is known as the Essentials from the Golden Cabinet (Jīnguì Yàolüè, 金匱要略)

Clinical Paradigm

It should be noted that in all these texts, diseases were not classified mostly according to organ systems the way they are in modern medicine. Rather, the Shāng hán Lùn would establish what we call in modern TCM as “pattern differentiation”. Let’s look at this example: a husband and wife went out on a date and “caught a bug”. They then developed what modern medicine call “the flu”. Treatment in modern medicine would be tailored towards perhaps giving an antiviral to go up against the virus or “bug” or give some medicines to treat individual symptoms such as fever or muscle aches.

But what if the husband had a high fever and sweating and gastrointestinal upset? And the wife had a mild fever with coughing and panting as well as nape and shoulder tightness. Both could be considered “the flu” and the treatments would be similar for both.

Not according to Chinese Medicine.

Chinese Medicine would recognize that the difference in symptomatology reflected a difference in the individuals response to the pathogen, and that treatment must take these into account. Hence, Chinese medicine would probably give totally different herbal formulas to the husband and wife, or use different sets of acupuncture points.

The TCM Practitioner tries to recognize the clinical pattern that the patient presents with and treat accordingly.

This clinical paradigm began with the Shāng hán Lùn. Future generations have developed their own schools of thought such as the aforementioned wēnbìng or Warm Disease Theory, with its own defined patterns and recommended treatments, but the building blocks of this method of diagnosis of treatment began here with Zhāng Zhōngjǐng. In fact, he did not just define immutable patterns, but taught others to recognize evolving patterns of imbalance and to select formulas according to how disease unfolds — from exterior to interior, excess to deficiency, cold to heat.

The Six Channels

Zhang revolutionized medical thinking by introducing the Six Channel (liù jīng 六经) framework — a dynamic model describing how disease progresses through the body’s yin-yang network. These six layers — Taiyang, Yangming, Shaoyang, Taiyin, Shaoyin, and Jueyin — represent functional stages of pathological transformation, not merely anatomical divisions.

The Three Yang Stages (Often exterior, excess, or heat patterns)

- Taiyang (Early Stage): The pathogen is on the surface. Key symptoms include a floating pulse, pain and stiffness of the head and nape, and an aversion to cold.

- Yangming (Interior Heat Stage): The pathogen has reached the stage where upright qi and pathogenic qi are fighting intensely. It is characterized by dryness-heat. If abundant heat is present, symptoms include a high fever, spontaneous sweating, and no aversion to cold but instead with aversion to heat, agitated thirst… and a surging pulse.

- Shaoyang (Half-Interior / Half-Exterior Stage): The pathogen enters shaoyang, disturbing the pivot mechanism. This creates the classic symptoms of alternating chills and fever, fullness and discomfort of the chest and rib-sides… a bitter taste in the mouth, a dry throat, and a thin wiry pulse.

The Three Yin Stages (Often interior, deficiency, or cold patterns)

- Taiyin (Spleen Deficiency Stage): This is the first stage of the three yin diseases. Spleen yang is unable to transport, resulting in a cold-dampness blockage. Symptoms include abdominal fullness with vomiting… and progressively worsening diarrhea with intermittent abdominal pain.

- Shaoyin (Heart & Kidney Deficiency Stage): This is a very serious stage where deficiency affects the heart and kidney. Key signs are a faint and thin pulse and a constant desire for sleep.

- Jueyin (Final Stage): This is the final stage of the transmutation process. It often forms a pattern of “upper heat and lower cold”. Symptoms can include wasting-thirst (xiāo kě, 消渴), qi rushing upward to the heart, heat-pain within the heart, and hunger without the desire to eat.

Also, diseases aren’t static. They “transmit and transmute” (chuán biàn, 传变). “Transmission” (chuán, 传) refers to the disease advancing from one jīng-channel to another. This progression depends on the strength of the pathogen and, most importantly, the strength of the person’s own “upright qi”.

The text also explains what happens when a person’s upright qi is very weak (a “direct attack”) or when two disease patterns appear at the same time (“combined disease” (hé bìng, 合病) or “overlapping diseases” (bìng bìng, 并病)).

A Living Legacy

The Treatise on Cold Damage is more than a historical text; it’s a living clinical manual. It established the diagnostic model of pattern identification , provided 112 foundational formulas that are still used today , and laid the groundwork for the entire practice of TCM today. In fact, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese scientists developed Qīngfèi Páidú Tāng (清肺排毒湯) to treat it. It is composed of four Traditional Chinese Medicine prescriptions: Mǎxìng Shígān Tāng (麻杏石甘湯), Shè’gān Máhuáng Tāng (射干麻黃湯), Xiǎocháihú Tāng (小柴胡湯), and Wǔlíng Sǎn (五苓散). All four were first found in the Treatise of Cold Damage.

Truly one of, if not the greatest medical book of all time.

References

Chen Ming, Zhou Gang, and Ryan Paul. Chinese Medical Classics: Selected Readings. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House, 2010.

Rong, F., Haoyu, H. E., Tao, T., & Hanjin, C. (2023). Long-term effects of Qingfei Paidu decoction in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 acute pneumonia after treatment: a protocol for systematic review and Meta-analysis. Journal of traditional Chinese medicine = Chung i tsa chih ying wen pan, 43(6), 1068–1071. https://doi.org/10.19852/j.cnki.jtcm.20230904.001

Dr. Tan-Gatue is a Doctor of Medicine, Certified Medical Acupuncturist and a Certified Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioner.

He is currently a Clinical Assistant Professor at the University of the Philippines College of Medicine, Section Head of the Section of Herbology at the Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine of the Chinese General Hospital and Medical Center in Manila, and a member of the National Certification Committee on Traditional Chinese Medicine under the Philippine Institute of Traditional and Alternative Health Care under the Department of Health. He was just recently appointed Associate Editor-in-Chief of the World Chinese Medicine Journal (Philippine Edition) and elected to the Board of Trustees of the Philippine Academy of Acupuncture, Inc.

He can be reached at email@acupuncture.ph

Discover more from Acupuncture Manila Clinic of Philip Tan-Gatue, MD, CMA, CTCMP

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

No responses yet