Note: This is a rewrite and expansion of a blog entry I wrote in 2013.

Introduction

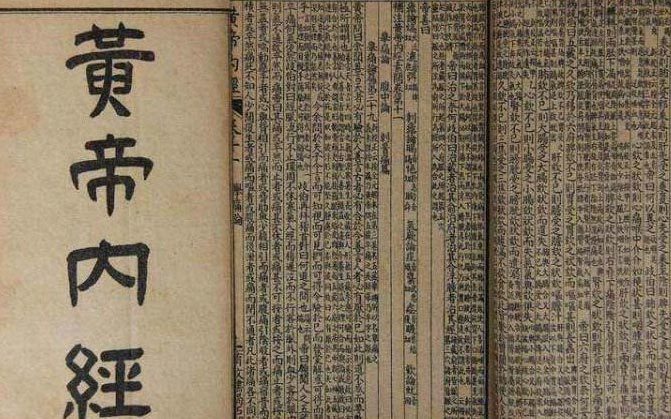

Of all the classical texts of Traditional Chinese Medicine, only two have been inscribed on UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register. The first one, in 2011, is the Huangdi Neijing (黃帝內經), otherwise known as the Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine, Yellow Emperor’s Internal Classic, Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Medicine, among others.

Nei (内)means “interior” or “internal” as opposed to “wai” (外) which means “exterior” or “external”. To illustrate its meaning, airplane flights in China can be divided into “guonei” (国内)- or “inside the country” and “guowai” (国外) or “outside the country. Neijing can mean internal classic – referring to internal medicine as in the modern sense. Internal Medicine as a specialty is called “neike” (内科) – “internal science” while surgery is called “waike” (外科)- “external science”. Before this confuses us, recall that surgery in both the east and west during ancient times was pretty much limited to cleaning and closing wounds, amputations, draining abscesses and the like. These were all considered “external” procedures as opposed to dealing with the internal organs.

It is said that a book called the Huangdi Waijing (黃帝外經) also was widely used in the past. However, no copies of this book has survived to the present day.

About the text

The Neijing traditionally was ascribed to the ancient and legendary Yellow Emperor or Huangdi. The mythology dictates that the Yellow Emperor (2698-2589 BC) wrote it personally. Historical research has shown that this classic was probably compiled over the course of several years by several authors during the Warring States Period (475-221 B.C.) The book is also traditionally divided into the Su Wen (素問), “Plain questions” and the Ling Shu (靈樞), “Divine Pivot”.

The Su Wen is the first part and is composed of 9 volumes with 81 chapters. Why 81? It is said that it has 81 chapters because 81 is 9 x 9. Apparently the ancients had this thing for numerology. Unfortunately, only 8 volumes were left after the ravages of the wars of the Three Kingdoms era. The version that survives up to now was compiled in the Tang Dynasty by Wang Bing (王冰)and even this edition was compiled again with notes and additions by Lin Yi (林億) in the Northern Song Dynasty. We no longer have this text in the original form, but we can be assured based on other books similar to it that the content is generally preserved.

The content of the Su Wen is written in dialogue form, with the Emperor Huangdi asking questions of his physician Qi Bo. Hence, the term, “Plain Questions” or “Simple Questions”. The book deals with the basic tenents of Chinese Medicine such as yin and yang, the five elements, qi, blood and vital substances and more. In addition, this book gives early descriptions of body parts, which shows that as early as this time Chinese physicians conducted dissections on the human body. The Ling Shu elaborates more on acupuncture points and techniques, the meridian system.

Significance

The Neijing’s main differentiating point from other contemporary medical texts of the time can be summarized thus: man did not get sick because of magic spells, curses, or incurring the anger of the gods, or the like. Man got sick by not living in harmony with nature.

In the first chapter of the Su Wen, Huangdi clarifies to Qi Bo that man used to be able to live a hundred years, but at their present time people get sick and are decrepit at the age of fifty. He then asks,

“Is this because the world has changed, or is it because people have lost the correct way of life?” (“時世異耶?人將失之耶”)1

Qi Bo replies:

“In high antiquity, those who knew the Way, they followed yin and yang and they corresponded to the arts of calculation. Their food and drink were measured, their rising and resting had regularity. They did not engage in wanton activities, and so they were able to keep their physical appearance and spirit together, and to complete their allotted lifespan, living one hundred years before departing. (上古之人,其知道者,法於陰陽,和於術數,食飲有節,起居有常,不妄作勞,故能形與神俱,而盡終其天年,度百歲乃去)2

Nowadays, people are different. They use wine as if it were (ordinary) beverage, they behave in a wild and undisciplined manner. When they are drunk they enter their sleeping chambers; in their desires they exhaust their vital essence; they dissipate their true qi. They do not know how to hold on to fullness; they are not able to control their spirit. Devoted to amusement, contrary to the joy of life, their rising and resting has no regularity. Therefore, already at the age of fifty, they decline.”(今時之人不然也,以酒為漿,以妄為常,醉以入房,以欲竭其精,以耗散其真,不知持滿,不時御神,務快其心,逆於生樂,起居無節,故半百而衰也)3

Note what Qi Bo says. people get sick by a) abusing alcohol, b) abusing sex, c) “work hard play hard” without taking time to rest and recuperate, d) sleeping and rising at irregular hours.

In other words: lifestyle.

We are not helpless peons who get sick or stay healthy on the whim of the cosmos or at the will of heavenly deities. Health is the result of conscious efforts to live in harmony with the principles of nature: eat right, dress appropriately for the climate, exercise adequately but have time for recharging.

Of course, this isn’t a simple task. That is why when we do get sick, the Neijing gives principles on how to understand what’s happening to cause the disease and elaborates on principles of how to approach the solution to the problem. The text provides the basis for TCM’s understanding of the meridians, the internal organs, the five elements. It has become the basis for a myriad of schools of thought regarding Chinese Medicine – The Cold Damage School, the Spleen and Stomach School, The Warm Disease School – all have their basis on the Huangdi Neijing.

Conclusion

Given its place in the history and development of Chinese Medicine, we therefore see why the text is given such honor and praise. Truly it deserves its place in the UNESCO Memory of the World register. For two thousand years, the Huangdi Neijing has served as the cornerstone of Chinese Medicine. May it’s teachings and principles last for thousands of years more.

References

Unschuld, P. U. (2003). Huang Di nei jing su wen: Nature, knowledge, imagery in an ancient Chinese medical text.University of California Press.

Footnotes

Dr. Tan-Gatue is a Doctor of Medicine, Certified Medical Acupuncturist and a Certified Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioner.

He is currently a Clinical Assistant Professor at the University of the Philippines College of Medicine, Section Head of the Section of Herbology at the Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine of the Chinese General Hospital and Medical Center in Manila, and a member of the National Certification Committee on Traditional Chinese Medicine under the Philippine Institute of Traditional and Alternative Health Care under the Department of Health. He was just recently appointed Associate Editor-in-Chief of the World Chinese Medicine Journal (Philippine Edition) and elected to the Board of Trustees of the Philippine Academy of Acupuncture, Inc.

He can be reached at email@acupuncture.ph

Discover more from Acupuncture Manila Clinic of Philip Tan-Gatue, MD, CMA, CTCMP

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

No responses yet